Ancient Chinese Calligraphy: Beyond the Masterpieces

While famous calligraphers like Yan Zhenqing and Su Shi are celebrated, historical artifacts from Dunhuang reveal that ordinary people in ancient China also struggled with calligraphy, challenging the myth that all ancient Chinese had beautiful handwriting.

The discovery of ancient manuscripts in Dunhuang, China has provided fascinating insights into the real state of calligraphy among common people during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). While history celebrates master calligraphers, these archaeological finds tell a different story.

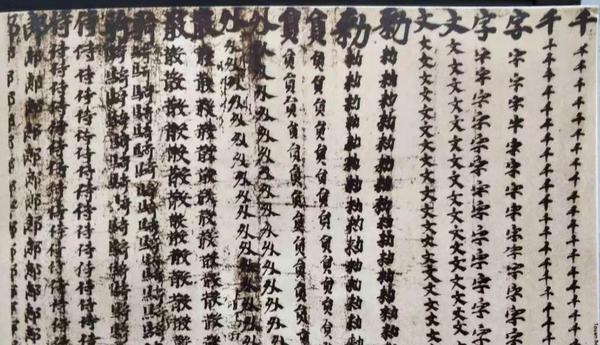

The Dunhuang manuscripts include numerous practice sheets where students repeatedly wrote the same characters, much like modern calligraphy learners. These documents show varying levels of proficiency, with many displaying awkward strokes and unbalanced compositions. One particularly telling example is a practice copy of the famous “Lantingxu” preface, abandoned midway likely due to the writer’s dissatisfaction with their work.

The widespread nature of calligraphy education in ancient China is evident from the “Practice Writing Miscellany” texts found in Tang Dynasty scrolls. Teachers would write model characters from right to left at the top of the paper, requiring students to copy each character 30-50 times to master the structure. These practice sheets often include teachers' corrections and comments, demonstrating that learning calligraphy was a structured but challenging process.

Even historical figures renowned for their accomplishments struggled with writing. The case of Empress Cixi’s court documents from 1865 reveals numerous errors and basic-level writing skills, despite her elevated status. Similarly, manuscripts by Song Dynasty official Sima Guang show relatively ordinary penmanship, suggesting that even educated officials did not necessarily excel in calligraphy.

Archaeological discoveries from Dunhuang have also unearthed examples of daily writing and religious texts with varying levels of skill. Buddhist sutra copies commissioned by ordinary people display modest calligraphic ability, indicating that professional-level writing was not commonplace.

These findings challenge our modern romanticization of ancient Chinese calligraphy. While exceptional works by master calligraphers have been carefully preserved through history, they represent the pinnacle of achievement rather than the norm. The Dunhuang manuscripts reveal that most ancient Chinese people, like modern learners, had to work diligently to improve their writing skills, and many never achieved the artistic heights we associate with classical calligraphy.

The preservation of these imperfect works provides valuable historical context and offers encouragement to modern calligraphy students. They remind us that mastery requires dedication and practice, and that even in ancient China, the journey to calligraphic excellence was filled with countless imperfect attempts.