Word Origins and Food Terms in Chinese and English

An analysis of non-intuitive word relationships in Chinese and English languages, focusing on food terminology and animal products, with special attention to historical influences and cultural differences.

The relationship between words and their meanings often reflects deep cultural and historical patterns that may not be immediately apparent. This is particularly evident in how different languages name food products and their sources.

In English, certain animal meat terms demonstrate a fascinating linguistic phenomenon. For instance, the words ‘cow’ and ‘beef’, ‘pig’ and ‘pork’, ‘sheep’ and ‘mutton’ show no obvious connection despite referring to the same animal and its meat. This distinction emerged from the Norman conquest of England in 1066, when French-speaking nobility introduced their terms for prepared meats, while the Anglo-Saxon words remained for the living animals.

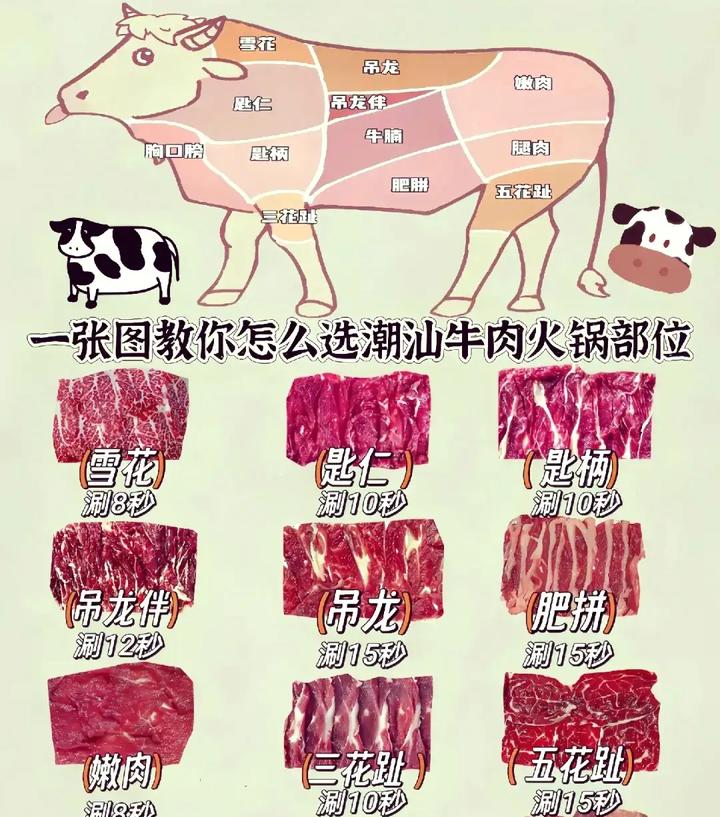

Chinese cuisine presents even more complex examples of this linguistic disconnect. In Chaoshan hotpot restaurants in China, menu items like ‘diaolong’ (hanging dragon), ‘shangxin’ (upper heart), and ‘xianrou’ (fresh meat) require local knowledge or research to understand their ingredients. These poetic or metaphorical names often obscure rather than reveal the actual ingredients.

The phenomenon extends beyond meat products. In Chinese, ‘rice’ has different terms for its growing form (dao) versus its edible form (mi). Similarly, sesame oil is called ‘xiangyou’ (fragrant oil) in Chinese, though the character ‘xiang’ (fragrant) bears no visible relationship to ‘zhima’ (sesame).

Traditional Chinese medicine provides striking examples of non-intuitive naming. ‘Yemingsha’ (night-bright sand) gives no indication of its bat excrement origin. ‘Renlongbai’ (human dragon white) and ‘wulingzhi’ (five-spirit fat) similarly obscure their actual sources.

Agricultural terms demonstrate this pattern as well. ‘Niuxi’ (cow’s knee) refers to a medicinal herb with no relation to cattle. ‘Tianniu’ (sky cow) names a type of beetle rather than any bovine species. These terms highlight how Chinese vocabulary often prioritizes poetic or cultural associations over literal description.

The sophistication of these naming conventions often correlates with social status and cultural refinement. Just as medieval English distinguished between common and noble terms for meat, Chinese traditionally maintained separate vocabularies for elite and common usage. This linguistic stratification served to mark social boundaries while enriching the language’s expressive capacity.

Modern global commerce has added another layer of complexity through borrowed terms and transliterations. Words like ‘qishi’ (cheese) in Chinese show no obvious connection to dairy products, just as English ‘ketchup’ gives no hint of its origins in Chinese fermented fish sauce.

This linguistic phenomenon reminds us that language is not merely a tool for literal description but a complex cultural artifact that preserves historical relationships, social distinctions, and cultural values in ways that may not be immediately apparent to speakers or learners.