Why Pinyin Omits Umlaut in Chinese Characters with J, Q, X

A linguistic exploration of why Chinese Pinyin omits the umlaut (two dots) when ‘ü’ follows consonants j, q, and x, tracing back to historical printing limitations and evolving standardization of Chinese phonetic notation.

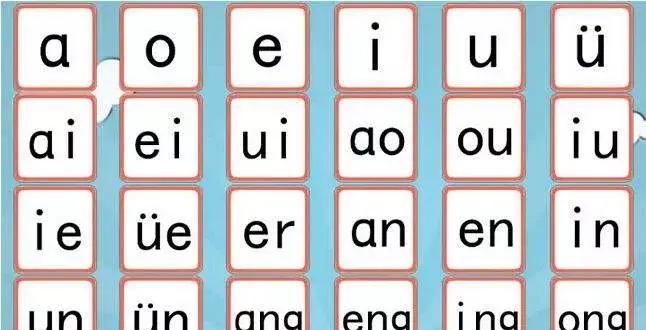

The seemingly peculiar practice of omitting the umlaut in Chinese Pinyin when ‘ü’ follows j, q, and x has deep historical and practical roots in the development of Chinese language standardization. This convention, while appearing arbitrary to newcomers, reflects thoughtful considerations in the evolution of China’s phonetic system.

The practice originated from practical printing constraints in the early days of Chinese typography. The umlaut mark (two dots) above ‘ü’ presented significant challenges in traditional lead-type printing. These dots were separate pieces that needed precise positioning, making them susceptible to damage and misalignment. Moreover, they created aesthetic issues in typesetting, particularly when combined with certain consonants.

However, the retention of this convention in the modern digital era stems from a crucial linguistic feature: the sounds represented by j, q, and x can only be followed by ‘ü’ and never by ‘u’ in standard Chinese pronunciation. This unique constraint makes the umlaut redundant in these specific combinations, as there is no possibility of confusion. The pronunciation remains unambiguous even without the diacritic marks.

Beyond technical considerations, this simplification aligns with broader principles of Chinese Pinyin design. The system aims to balance accuracy with practicality, often favoring simpler written forms when they don’t compromise phonetic clarity. Similar simplifications exist throughout the system, such as the omission of ‘u’ in “uo” after b, p, m, and f.

For native Chinese speakers, this convention poses little difficulty as they intuitively understand the pronunciation rules. However, foreign learners often find it challenging initially, as it requires memorizing additional rules beyond basic phonetic principles. This highlights an interesting tension in the system between efficiency for native users and accessibility for language learners.

Modern technology has largely eliminated the original printing constraints, yet the convention persists due to standardization and widespread adoption. This exemplifies how writing systems often retain historical artifacts even when their original practical justifications no longer apply, similar to the QWERTY keyboard layout’s persistence in the digital age.

Japanese and Korean writing systems, which also use modified Latin alphabets for phonetic notation, have faced similar challenges in representing sounds absent from the original Latin alphabet. Their solutions often parallel the pragmatic approach taken by Chinese Pinyin, demonstrating common patterns in phonetic adaptation across East Asian languages.